Table of Contents

1. Introduction

An article taken from Scandinavian Inflatable Club (Skandinaviska gummibåtsklubben) membership magazine 1998 issue 4.

It must be pointed out that before 1998, in Sweden, there were very few RIBs. Knowledge about them was sparse.

Something that made it extra exciting and fun to start designing and construct a RIB. And also a feedback from the designer 25 years (!) after the RIB was built.

I’m very honoured that this article has been allowed to get published on RIBs ONLY and I would like to thank these RIB passionates for their outstanding work to bring this unique story to you:

Text and construction: Mats Ryde, Sweden

Translation, epilogue and editing: Mårten Danielsson

2. To Build a Plastic Hull for a “Rubber Boat”

Why do you build a plastic hull for an inflatable boat? For me, it was an idea that I have been pondering for a few months.

If you look at the Coast Guard or the sea rescue, they have “rubber boats with plastic hulls”, also called RIB (Rigid Inflatable Boat). When you combine the rubber boats’ pontoons with the rigidity of the plastic hull, you get a very good combination.

The rubber pontoons provide both stability and superior buoyancy. The plastic hull adds course stability and better gait in rough seas as well as a solid surface to attach equipment to, steering console, frame etc.

This sounded very appealing, but is it practically feasible Before embarking on a project like this, you have to devote yourself to some research and ask yourself some questions.

3. Is it Possible and Are They Worth it?

Is it possible to mount a hull on my rubber boat? Is it worth the effort to build a plastic hull for my rubber boat? I do not think it is worth the trouble to build plastic hulls for boats under 4 meters.

This is because large boats are usually inflated throughout the boating season and these have associated boat carts. The main advantage of small boats is that they are collapsible.

Do I have a good room to work in? Good ventilation is important because polyester plastic emits strong and dangerous fumes. Is an engine change to a higher power necessary to compensate for the increasing weight?

Once I had made up my mind, it was time to start some research and planning.

I found out if there were any inflatables in my particular boat size with a plastic hull. I read brochures, boat magazines etc. I studied “real” R.I.B.’s to see how the hull attachment and design were implemented.

I talked to people who work with the manufacture of plastic boats, they could give tips about the plastic work and mould building.

4. Negative environment for a positive project

And most of all I did not care about people who said it was not feasible! There were skeptics around me who told me it was an impossible project.

42 knots at the first test ride gives its clear answer to this statement… Nothing is impossible!

5. Hull Planning

Before building the mould, I studied the hull of factory-made RIBs. I also read a lot of newspaper articles on the subject.

You can roughly divide the hull into two types. The sharp V-hull, which is found on high-speed boats, gives a boat that cuts through the waves and does not stomp so much in high waves. However, these boats have a tendency to become wobbly at high speeds because they have such a small surface in the water.

The second type has a smaller angle on the hull, which helps the boat to be more stable in the water, but it stomps more in waves. When I would make moulds I chose to make the hull sharp in the bow and flatter in the stern. This means that the boat cuts decently in the waves while maintaining stability, which was my hope.

The next step was to make the step strips, which make the boat “lift” out of the water. Step mouldings have looked the same for probably 30 years, but recently they have become more bowl-shaped.

The new design means that the water is directed downwards instead of to the sides; the boat then gets more lift. I glued wooden slats with the right step strip contour to the finished form.

6. Mould

Male-shape mould made of plywood before plasticising – picture 1

The first thing I did was measure the boat’s width, which was 30 cm along the entire inside, which I then drew on the floor.

I chose to make an outside mould where you put the plastic on the outside of the mould, instead of inside. You then see exactly what the hull looks like when it is finished.

On my drawn floor measurements, I put frames with the right bottom angle at 30 cm intervals. On the frame I nested a thin, flexible plywood (see picture 1). Note the wings on the side the form. I made these 10-15 cm wide wings so that the pontoons would have something to rest on.

I then sanded the plywood so that all sharp edges disappeared. I made the shape 10 cm longer than the boat’s inner dimensions because it would facilitate the fit between the hull and the transom (see picture 2).

Rear transom before sanding the plastic – picture 2

7. Plastificiation

I started by lubricating the mould with mould oil so that the plastic would come off easily. Then I laid layer after layer with plastic fiber mat and polyester. It is of great importance to saturate the fiberglass properly with polyester between each layer.

It is important to use one aluminum roller to push out all the air between the fiberglass mats. I laid all the layers at the same time to get a stronger laminate. After that, it was just to the let the polyester harden for two to three days.

Polyester plastic can become very hot during curing and, if you are unlucky, self-igniting.

After finishing hardening, I removed the hull from the mould. This was a bit tricky, but with mild violence it worked out. I palletised the hull on the right keel because it is flabby before the frame comes in place.

I made the frame in 7 mm marine plywood which I plastered at 100 cm intervals. In the joint between frame and hull, I laid six layers of fiberglass mat because the frame must withstand large forces and make the hull rigid.

On the inside of the hull, I plasticized a 20 cm high railing edge around the entire boat to make it completely waterproof.

In the stern I plasticized the railing with the transom and on its outside I laminated 5 x 5 cm wooden slats which the rubber would then be screwed into.

8. Grinding and Filling

The grinding work became more extensive because the choice of laying the plastic on top of the mould leads to an uneven outer hull. After sanding, I wet-dried the bottom with tins so that the top coat would get a good grip. Top-coat is a 2-component putty that forms a hard surface after curing and facilitates the sanding work. On the top coat I painted a hard 2-component paint to get a smooth bottom surface.

9. Adjustment of the Pontoons

I turned the inflatable boat upside down. Then I cut off the old rubber cloth at the bottom, but I left a 10 cm wide piece along the pontoons and a triangular piece in the bow.

I stepped the triangular piece over the lining of the plastic hull and I tightened the pontoons backwards in the right position.

I plasticised the transom with two so-called knees to get a strong connection between the hull and the transom (see picture 3).

Mounting the knees between the bottom of the hull and transom as reinforcement – picture 3

Since the hull angle was sharper on the plastic hull than on the old rubber bottom, I plasticized an additional piece under the old transom (see picture 2).

Then it was time to screw the leftover rubber cloth into the wooden slat, previously described. I pre-drilled holes for the screws because it is difficult to screw through plastic laminate.

10. Deck Floor

Inside the boat, I mounted a frame of wooden slats (see picture 4) in which I plasticized the hull. In this frame I screwed fixed floorboard of aluminum.

The choice of aluminum was made because it is a strong, durable and easy-to-work material.

Rules for mounting floorboard – picture 4

Rules for mounting floorboard – picture 4

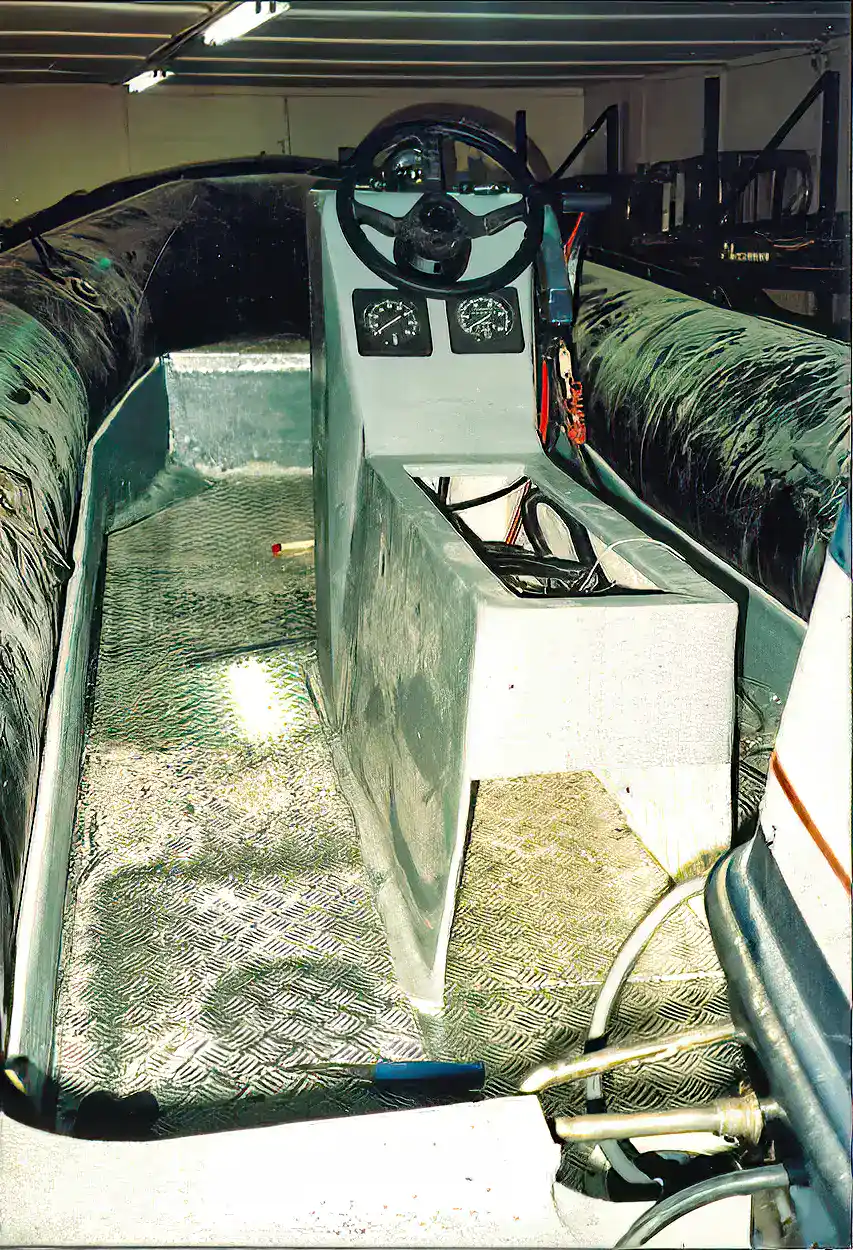

11. Steering Console

Building the steering console

To get a comfortable driver’s seat, I chose to make a console that you have a border over. When driving in high seas, you must be able to sit or stand comfortably with a real backrest to lean against.

Building the steering console

I made it so long that you could sit two people, as well as a map table standing vertical against the driver’s backrest.

Building the steering console

Building the steering console

12. Epilogue

Like many enthusiasts, the builder in the article, Mats Ryde from Sweden, offers to help others with knowledge and tips, but when the article was written in 1998, we skip contact information.

Mårten Danielsson has in a true journalistic spirit tried to contact Mats Ryde without success and he is unfortunately not on Facebook either.

But after countless attempts and detective work, success ensued. The RIB builder was as surprised and perhaps flattered when I caught him on a Sunday night.

“I did not think anyone would contact me 25 years after I built my RIB. It was really unexpected” according to Mats Ryde.

Mats Ryde says that as a fearless 20-year-old he worked in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia as a diver and became curious about RIBs.

He really knew nothing about plastic, boat building or hull shape. So he contacted several boat designers and got advice on how to build his boat and he had to borrow a small garage. He then thought: “it can not be that difficult”. Little did he know then that the often over 50°C degree heat in Jeddah would not make it easier…

The pontoon was a problem that had to be solved. At a boat scrap yard in Saudi Arabia, he found what he was looking for, a well-used and scrapped professional inflatable boat of the brand Zodiak MK V HD. But most important of all – the pontoon was intact, but badly worn by years of hard service and extremely strong sunlight.

The construction period lasted about a year on his spare time. When the job as a diver in Saudi Arabia ended, the self-designed RIB was sent home to Sweden in a container.

Once back home in Sweden, the final assembly of the boat lasted for about four weeks. Only after that could the RIB be launched for the first time.

“It was exciting to see how the boat would behave. It turned out to be very easily driven and fast, with around 50 knots as top speed. Really fun!” Mats Ryde declares.

nearly ready working on the pontoon problem

But like all fun, this also ended too quickly – already after 20 hours. The pontoon dried out by the sun began to become increasingly brittle and patched.

So the young designer decided to “release” the RIB to a distant relative who said he wanted to renovate the tube.

It is many years ago now and Mats Ryde says that he does not know what happened after that with his home-built RIB.

The RIB finally out at sea

Someone who has been a professional diver and built his own RIB already as a 20-year-old, what is he doing today in 2022?

“I work as a Staff Photographer at the Swedish Sea Rescue Society and previously as Technical Support in the same organization” Mats Ryde reveals.

It feels as the adventurous Mats Ryde has ended up in the right place in his professional life.

13. Specs

| Length | 585 cm |

| Width | 248 cm |

| Weight | 450 kg rebuilt incl. engine |

| Tube | from Zodiac MK V HD |

| Tube diameter | 63 cm |

| Engine | Yamaha 85 hp |

| Propellor | Yamaha, aluminum, 13×17 inches |

| Top Speed | 47-50 knots after fine tuning |